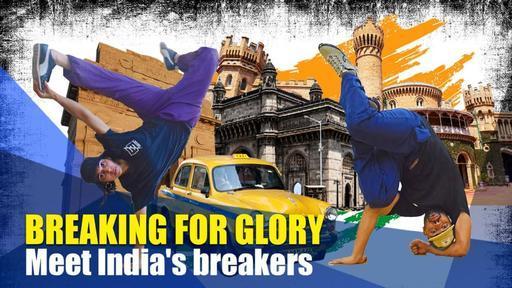

The first thing you notice when you walk into the room is the nonchalance with which everyone is grooving to the beat. It’s a muggy Mumbai evening in April 2019, the coronavirus and social distancing are almost a year away and the mirrored room in this dance studio in suburban Andheri West is teeming with 20-somethings, teens, and tweens. They are all wearing baggy T-shirts, tracksuits, and sneakers; some have their hair braided in cornrows, others have trucker or snapback hats on.

The DJ, manning a giant sound system on one side of the room, starts ramping up the volume. The tempo picks up, the group splits into two; two M.C.s and a rapper reel off verses – freestyle – in Hindi and English; and a relatively older B-boy from one of the two competing factions sets the ball rolling by launching himself onto the centre of the floor with a dizzying – and potentially neck-breaking – sequence of power moves.

——Advertisement starts here ——

NRIForShaadi.com World’s #1 App for NRI Matrimony. Thousands of members near your GPS Location. Download from NRIApps.com

NRIForShaadi.com World’s #1 App for NRI Matrimony. Thousands of members near your GPS Location. Download from NRIApps.com ———Advertisement ends here ———

‘Babymill’, ‘windmill’, ‘swipe’, ‘halo’, ‘headspin’ — in that order.

Repeat.

‘Air flare’, ‘hand slide’, ‘1990’, ‘U.F.O’ — all in a swift, single motion.

On come more improvisations.

More imagination.

And more imaginatively named variations.

The tweens, several of them from Dharavi, Asia’s largest slum, watch in awe; the older ones, a mix of college-going dance enthusiasts, professional dancers and dance instructors from Mumbai, Delhi, and Bengaluru, and mundane semi-professionals with day jobs aspiring to be full-time dancers, shout in appreciation. Strength, stamina, creativity, precision come together in sync — a typical sight in all competitions, referred to as “battles”. The performance on view is years of self-teaching, learning, and unlearning crystallised into a highly skilled blend of artistry and athleticism.

Welcome to India’s breaking community, part of the wider universe of breaking – more widely and informally known as breakdancing. The radical urban dance style journeyed from New York City in the early 1970s to all corners of the world, and is now headed for its grandest stage: the 2024 Olympic Games in Paris.

Breaking down India’s Olympic dream

The Mumbai meet-up was organised by Arif Chaudhury aka B-boy Flying Machine, India’s best-known breaker, to commemorate ten years of his being on the scene. His name and fame attracted breakers’ crews from Delhi and Bangalore; the event featured free workshops by Chaudhary, battles between Mumbai-based rappers and of course all the breaking battles.

Breaking in India has been an unorganised dance-sport – in the conventional sense – for more than a decade now, but there’s an informal understanding within the community that makes up this subculture. Chaudhary, 24, started out in 2007, representing and being groomed by SLUMGODS. This was an artists’ collective based in Dharavi – the name a reference to the movie Slumdog Millionaire – and founded by India’s first-generation breakers, B-boy Simon Talukdar and HeRa, with Akash Dangar, a young breaker from Dharavi and Indian-American rapper Mandeep Sethi. If hip-hop came from the ghettos, breaking in India, they realised, would find its inspiration in the Indian equivalent – places like Dharavi.

Chaudhary had begun training about two years earlier, on the streets and in the parks of Mumbai’s Jogeshwari area, days after he first learned of breaking through a video he watched of a B-boy performing at an international competition.

“A large number of breakers take up contractual jobs as background dancers in ads or movies in Hindi or regional film industries. The pay is meagre; worse, performers like breakers and parkours are often treated as mere props, not even fillers. There’s not much dignity in the way the industry uses us.”Arif Chaudhury aka B-boy Flying Machine

He won the national championships, organised by Red Bull, three times since its inaugural edition in 2015 to earn his place at the top of the Indian scene, representing the country in high-profile battles in Austria, the Netherlands, Slovakia, China, Japan and Taiwan. He now has a bird’s-eye view of the sport and can look at it with some emotion, and with a sense of pragmatism.

“Ours is a breathing, living community. Our battles have rules, our training is regimented, and we have ethics we try to obey, even though on the outside most Indians think of us as aimless street dancers or circus people doing ‘tricks’,” Chaudhary tells . “And now that it’s in the Olympics people will question whether to think of breaking as just an art or a sport or both. What matters to us most, though, is we try and uphold the original essence of breaking: the communal feeling of being an alternate form of expression, rebellion, creativity, athleticism.”

What does the future look like? “Indian breakers still have some way to go before we can rise to the top, globally,” Chaudhary says. “But you also have to understand that we have come this far mostly by ourselves, with little to no external support. Can the prospect of having Indian representation in the Paris Olympics alter our fate? Definitely. The title of an Olympian is a big deal after all.”

No free breaks

Breaking – and much of the ever-evolving hip-hop tradition at large, of which breaking, rapping, DJing, and graffiti are the four elemental components – has grown into a symbol of youth culture in India over the past decade. Several corporate brands have linked up with the most promising names in the community, bringing in rare full sponsorship or small-scale supplemental income opportunities.

Red Bull, for example, has played a role in developing the sport with their BC One event since 2015, giving it a sense of organisation. The event is known to attract breakers from across India – the metros, of course, but also Jalandhar, Shillong, Guwahati and Hyderabad. A year ago, they brought the BC One World Finals – an annual global tournament run by them, and different to the official World Breaking Championships. The event is staged in a different country every year, either in emerging markets with a strong breaking scene or locations with a legacy, and the Mumbai event had the world’s 32 best breakers, men and women, competing over three days.

But it isn’t enough. “It’s difficult to make a living solely through breaking in a country like India,” says Chaudhary, one of the few breakers on private sponsorship – his association with Red Bull includes financial support, provision of costs of training in studios in Mumbai and two-way international travel cover for competitions.

Most breakers, underlines Chaudhary, work day jobs to sustain their passion for the dance-sport. Some offer coaching classes, which have mostly moved online in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, while others are hired on short-term contracts as youth influencers for clothing and fitness brands.

“A large number of breakers take up contractual jobs as background dancers in ads or movies in Hindi or regional film industries,” says Chaudhary. “The pay is meagre; worse, performers like breakers and parkour [practitioners] are often treated as mere props, not even fillers. There’s not much dignity in the way the industry uses us.”

Breaking through bureaucracy

Breaking made its debut as a medal event at the 2018 Youth Olympic Games in Buenos Aires, with the International Olympic Committee-recognised World DanceSport Federation (WDSF), which generally oversees ballroom dancing competitions, assuming the role of its governing body. India returned from the Games with 13 medals, their best-ever haul at any Youth Olympics, but had no representation in breaking.

Many breaking veterans in India believe that the lack of a federation overseeing breaking in the country may have robbed promising young breakers of the chance to immerse themselves in what could have been a foundational experience at a pioneering event.

Biswajit Mohanty, the general secretary of the WDSF-affiliated All-India Dance Sport Federation (AIDSF), hopes the addition of the Olympic cachet will change the narrative around how breaking is administered in the country in the future.

“The AIDSF has held 10 national championships to date. Breaking has not featured in any of them, but we are drawing up plans to include breaking in the upcoming editions and invite coaches from abroad,” Mohanty says.

The AIDSF is not a member of the Indian Olympic Association (IOA), but “now that breaking is part of the Olympic movement as the first dance-sport [discipline],” Mohanty hopes it could make the IOA consider fielding breakers at both the Youth Games and the Summer Olympics.

“People on the road often take great pride in telling me that they had mistaken me for a boy because I usually keep my hair cropped and wear unisexual active wear, or for having put on muscle as I started becoming fitter due to rigorous training for breaking.”B-girl Johanna Rodrigues

Breaking stereotypes: Dangal style

There’s another role that breaking has played, and can continue to play in the future: opportunities for women. Johanna Rodrigues, one of the more known B-girls in India, believes that the gender-equal representation of breakers, 16 men and as many women competing for gold in two separate events, at Paris 2024 could be a much-needed shot in the arm of the fledgling demography of Indian B-girls.

“Being a girl in India sets you at a disadvantage only if you subscribe to that perception, but there’s no denying the obstacles it creates for us B-girls,” Rodrigues (24), who took part in last year’s Red Bull BC One World Championships, says. “There needs to be a gendered separation for now in breaking until the girls get enough of a platform and catch up on years of not even thinking like the guys did. And after a while they grow enough in confidence, get more aware of their abilities, boys and girls can compete in the same pool.”

Rodrigues works in Bengaluru as a yoga instructor and often combines breaking with moves from Bharatnatyam, the Indian classical dance form, and the ancient Indian martial art of Kalaripayattu. The prospect of Indian breakers competing at the Olympics, she says, could “legitimise what many people here often wrongly see as women doing a masculine dance.”

“People on the road often take great pride in telling me that they had mistaken me for a boy because I usually keep my hair cropped and wear unisexual active wear, or for having put on muscle as I started becoming fitter due to rigorous training for breaking,” says Rodrigues. “But I know from Dangal (the Bollywood biopic on the wrestlers, the Phogat sisters) that a lot of sportswomen receive this when our bodies change and we look stronger.

“That a B-girl from India could compete for a medal in the Olympics should encourage more young girls to try it out, more B-girls to compete against each other in India and form a community. Better still, parents, who have been [traditionally] unsupportive of their daughters breaking, at least, might stop discouraging them. That’s the first step to winning [a medal].”bjh